Note: Don’t Up Mess My Block, published in Thirty First Bird Literary Magazine, is an excerpt from my novel of the same name.

“We must do the thing that terrifies us most.”

Eleanor Roosevelt

I was dressed up like an Italian, with gold chains around my neck. Sweat poured from under my black wig as I pushed my way through the crowd. I shouted up at the French paratrooper. “European national!” I said, holding aloft my new EU passport. The gate of the embassy opened and I ran for the waiting helicopter.

We in the West take so much for granted – elected governments, honest police forces, functioning capital markets, pornography on demand. These are benefits of our civilization.

However, I believe it is the duty of us fortunate people to bring prosperity and democracy to the darker corners of the world. And I also believe in seeking out personal challenges, as evidenced by the above quote.

Which is why I was in the Republic of G——. I don’t spell out the name of this country for reasons that will be clear later in this narrative.

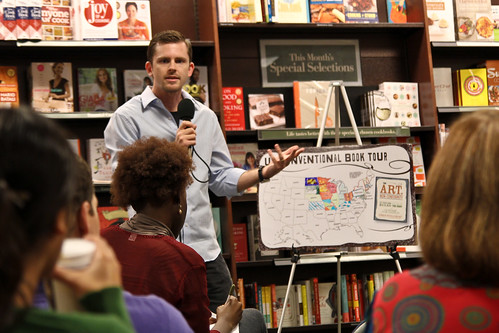

I had spent the past year in Hiltons and Hyatts from Akron to Long Beach, empowering audiences to heedlessly seize their dreams with my “Don’t Mess Up My Block” concept. Several articles had already been written about my idea and the response in the blogosphere had been very favorable. I started the tour lecturing to middle school business clubs and concluded by giving a presentation to more than a hundred passport clerks at the State Department.

After the applause died down in the Condoleeza Rice Auditorium, the director of the West Africa desk approached me with an interesting proposal. Would I be interested in applying my practicums of self-improvement in the Republic of G—?

I initially declined his offer. The Republic of G— is infamous, even by degraded African standards, for its corruption, state-sponsored violence and swarms of biting gnats. And for its “intractable civil war”. That was the phrase that was used more than any other in press accounts of this unfortunate sliver of a country.

Besides, I was making a comfortable living with my “Don’t Mess Up My Block” presentation. Based upon a late-night encounter with a hooker who told me to get lost, the root of my self-actualizing speech was to be loyal to your blind ambition, whatever the costs.

As I advised audiences to clear the deadwood (kids, family) out of their lives to achieve success, my speaker fee steadily climbed and was approaching the five-figure sum enjoyed by my mentor, Esalen.

Esalen was also my life coach at this time. I talked to him weekly, as we reviewed my goals and activities. Esalen took a keen interest in my life, especially when it came to my speaker fees.

“Soon, you and I will be on the same level!” I laughingly told him.

“You should take the State Department job,” Esalen responded.

I was silent, imagining my violent death in a green jungle at the edge of the equator.

“You should take it because it’s dangerous,” Esalen said, as if sensing my discomfort. “If you come back alive, you will be fearless. And if you don’t, well, lesson learned.”

We discussed the matter into the night, over the phone. Esalen was ensconced in the Four Seasons San Francisco while I lounged comfortably on the 800-count sheets of the Four Seasons Washington. My trajectory had taken me, in just a few short months, to the exalted level of inspirational speakers that Esalen occupied. My mentor believed that I needed a new challenge, something that would really stretch me. The fear of my execution at the hand of Maoist guerillas was a legitimate concern, for they had recently put to death a whole busload of bird-watchers from Nebraska, on perhaps the most ill-planned expedition ever mounted by the American Aviary Society.

“You’ve become too comfortable,” Esalen said. “You need to stretch.”

After several hours of argument, Esalen convinced me. I would go to Africa, because I could get killed. It was the type of challenge that I needed. Esalen seemed relieved that I was going to a war zone.

The next morning, I called the State Department. My contact was delighted. They had money they needed to “move” as he called it, before the end of the fiscal year. I would start immediately.

The next day, I was on a plane to Africa. After landing on a pockmarked runway, I was taken to the Presidential Palace. Lions roamed the grounds of the immense estate.

Columns of smoke lined the horizon, from villages that the guerillas were “purifying” of capitalism.

The Ruler, as he was referred to, listened to my presentation politely, almost docilely. This was a man who came to power in an early-morning putsch a couple years earlier. The elected President had been rousted from his bed and shot at poolside by The Ruler himself. At the time, he was known as Captain Mobumbo. Not one to delegate, he liked to handle matters personally. After his ascension to power, he beat the guerillas back to their highland bases. His methods were extreme, but successful. With his hands-on management style and disregard for the “rules” (like human rights), I likened him to a jungle Steve Jobs. He would be at home in any corporate boardroom in America.

Now, however, he needed help. The Western powers had cut off the line of credit he used to buy Kalashnikovs from the Ukraine. His methods had been a little too extreme. Amnesty International had discovered mass graves and assumed the worst. Anyone could’ve put those bodies there.

Without access to new weapons, The Ruler had lost his way. He was tentative, unsure, and the guerillas had crept out of the mountains and fought their way almost the length of the entire country, until they were nearly to the Presidential Palace itself. In the capitol, democracy blossomed, and with it came a swarm of critics biting at the ankles of The Ruler, like the fabled gnats of this swamp-laced land.

Where the people once saw blood and terror in his eyes, now they sensed weakness and confusion.

The man I saw wasn’t the stern-faced executioner of yore. He fiddled with prayer beads as I began my presentation. I told him about my encounter with a prostitute. “After I said I wasn’t interested, she told me to get off of her block,” I explained. “I was getting in the way of her success. I was messing up her block!”

The Ruler shared a laugh in his native tongue with his AK-carrying guards. As I outlined with him the idea that reaching your potential requires removing people from your block, his visage became serious. He leaned forward, as if hearing a good folk tale. I warmed to the task and smote the air with one hand.

“You must clear your block!” I shouted, willing the man into action.

The Ruler burst into applause, a smile spreading across his face.

“Marvelous! Simply marvelous!” he said. He then grew serious. He took me by the hand, squeezing it with just a hint of his legendary strength. “This is what the State Department wants?” he asked. His blood-red eyes stared into mine.

“Yes.” I believe in the practice of responding confidently to any question, even if you’re unsure about the answer. Doing so establishes your authority.

Did the State Department really want The Ruler to implement my ideas? It seemed like they did. The contract for services was unclear, with vague words like “education” and “outreach” scattered throughout its dozen pages. If State didn’t want “Don’t Mess Up My Block” adapted to G—- then why send me to the country?

If I was more adept at the murky world of diplomacy, I would’ve asked more questions. However, I was from the land of business consulting, where success is measured by speaking fees and muted applause in conference rooms.

The Ruler leaned forward. “The message is understood.” His eyes now blazed with newfound confidence. He strode out martially.

I returned to my room, lulled to sleep by the roar of lions, confident that I had earned every penny of my $25,000 remuneration.

The arrests began the next day. I saw it on BBC, shortly before The Ruler kicked the network out of the country. It was a wholesale roundup of his enemies. He called it, “Operation Don’t Mess Up My Block.”

My contact at State was furious. The Ruler apparently claimed that I, and, in extension, the U.S. government, had authorized this crackdown. The Ruler had explained to State that those arrested we’re messing up his block.

“This was just a public education grant!” my contact fumed. “You were just supposed to give a presentation on management techniques!”

“He asked for advice and I gave it to him.”

My contact made a guttural sound of anger and frustration. “I just had some money left in the budget that I had to spend! And now all of West Africa is destabilized.”

“Maybe,” I said, thinking quickly. “Maybe, West Africa needed to be destabilized, like a company needs a reorganization.”

The phone line cut off. The Ruler had shut down access to the outside world.

There was a knock at the door. The Ruler needed me.

“Thank you for your excellent counsel,” he said, resplendent in his uniform of tiger skins and peacock feathers. He occupied his throne as if he was immortal. “My enemies are now in jail. They were block messers. But, now, the opposition say that I mess up their block by putting their leaders in jail. They have called for a general strike. What do I do?”

I was improvising, when I am best. “There are unresolved pressures in your political system. They must be allowed to come out into the open, so that a solution can be arrived at.”

The general strike began and, within days, the country had run out of gasoline and food. The people were hungry and restive. The Ruler had shot all the leaders of the opposition so there was nobody to negotiate with. The streets devolved into running gun battles between soldiers and the opposition. Both sides were running out of food and ammunition. Meanwhile, the fires of the Maoist guerillas kept inching closer to the capitol.

A C-130 landed in the middle of the night and evacuated all Americans in the country. However, in an apparent oversight, I was not informed.

On a borrowed satellite phone, I got through to my contact at State. “Sorry about that,” he said. “We just forgot.”

“Can you get me out?” I asked. The boom of mortars was getting closer.

“Ask the French.” The line went dead.

The Ruler summoned me. He was feeding whole chickens to his lions. He held a bird aloft by its neck.

“This is the last chicken,” he told me. “No more chickens left for the lions. No beans left for the soldiers, either.”

We watched the lions fights over the chicken carcass, guarded by restive soldiers with machine guns.

“Hungry soldiers aren’t loyal,” he observed.

I proposed doing a listening session with the palace troops. I would facilitate and record their perspectives.

“I just need some whiteboards and markers.”

The Ruler considered the offer. “That will buy me some time,” he said.

The next day, I went down to the barracks. I had not been provided a whiteboard or a laser pointer or slides or even a laptop. The soldiers didn’t understand the point of the exercise. They remained in their bunks as I explained that I was to facilitate a discussion of the advantages and disadvantages of employment with The Ruler.

“Now, what is constructive feedback?” I began.

Suddenly, there was a roar from the airstrip. A DC-9 lifted up into the sky. On it was The Ruler and the country’s gold reserves.

The soldiers rushed outside and mindlessly fired their AKs at the departing aircraft. My situation no longer seemed tenable. The Ruler was en route to the south of France. I needed an exit strategy. Before the soldiers could return and vent their rage on me, I caught a car to the city.

The Charles de Gaulle, a rusty French aircraft carrier, loitered offshore, ready to evacuate European nationals. Vive le France, I thought. I knew that I had to think positively if I was to survive.

In the capitol, no bullets were left. The soldiers and the opposition had joined together to loot the city before the guerillas arrived.

How did I manage to get an EU passport? Networking, Third World-style. A taxi driver I bribed knew a local fixer who I bribed who knew a forger who I also bribed to get me an EU passport. The photo in the passport was of someone else, which is what necessitated that I wear a wig and gold chains in order to pass as Marco Lucchese of Palermo, Italy.

The French paratrooper didn’t even look at the large-nosed visage in the passport and compare it to my own more pleasingly symmetrical face. He just saw that I was holding the right-colored document in hand and waved me toward the parking lot where a helicopter was waiting.

As we lifted off, the city in flames beneath us, I reflected on the experience. After a client engagement, I always spend a few quiet minutes processing the encounter, as if I was meditating. What did I learn? What value did I provide? What’s my takeaway from the experience?

The helicopter banked hard to avoid a RPG as the other passengers on the flight screamed. The grenade exploded in a red blast a hundred feet away, nearly shaking us from the sky.

Maybe the Third World wasn’t ready for American-style personal empowerment? As we fled the continent for the safety of a waiting aircraft carrier, it was hard not to make that assessment. Had my ideas failed in Africa? Was “Don’t Mess Up My Block” not an appropriate strategy for a newly developing country?

We were now over blue waters dotted with fishing boats fleeing the chaos of the Republic of G——.

My ideas were sound. The implementation was faulty. The Ruler had applied them incorrectly. By jailing all of his enemies, he had destabilized the country. His enemies weren’t the one who were messing up the block. In fact, it was The Ruler who was standing in the way of his country’s ultimate embrace of democracy and capitalism. Only by getting rid of himself could the country succeed. Despite the chaos and the looting, the Republic of G—- could now progress into a brighter future.

I could see the PowerPoint slides now, as I explained things to the State Department. This would be an important lesson for them to record and understand. Perhaps I would be invited to give a lecture series to Foreign Service Officers around the world.

With my African adventure, I had discovered something important. I had stretched myself, as my mentor Esalen wished, and came away from the experience with a vital lesson. “Don’t Mess Up My Block” was a compelling meme, one that animated the leader of a country to change everything. That was a truth that deserved to be heard beyond just the few people I could reach through my public speaking.

Excitement filled me as the Charles de Gaulle came into view, trailing an oil slick a hundred miles long. My fellow passengers were crying in relief at their deliverance. I, however, had work to do.

The helicopter landed with a hard thump aboard the aircraft carrier. Deck personnel rushed us off the craft, its blades still spinning. The chopper was going back to rescue more Europeans.

I believe in striking while the iron is hot. Inspiration is a fickle mistress.

While the other refugees were calling out their thanks in a polyglot of languages, I grabbed the first sailor I saw.

“Can I get a laptop?” I shouted. “I have a book to write!”